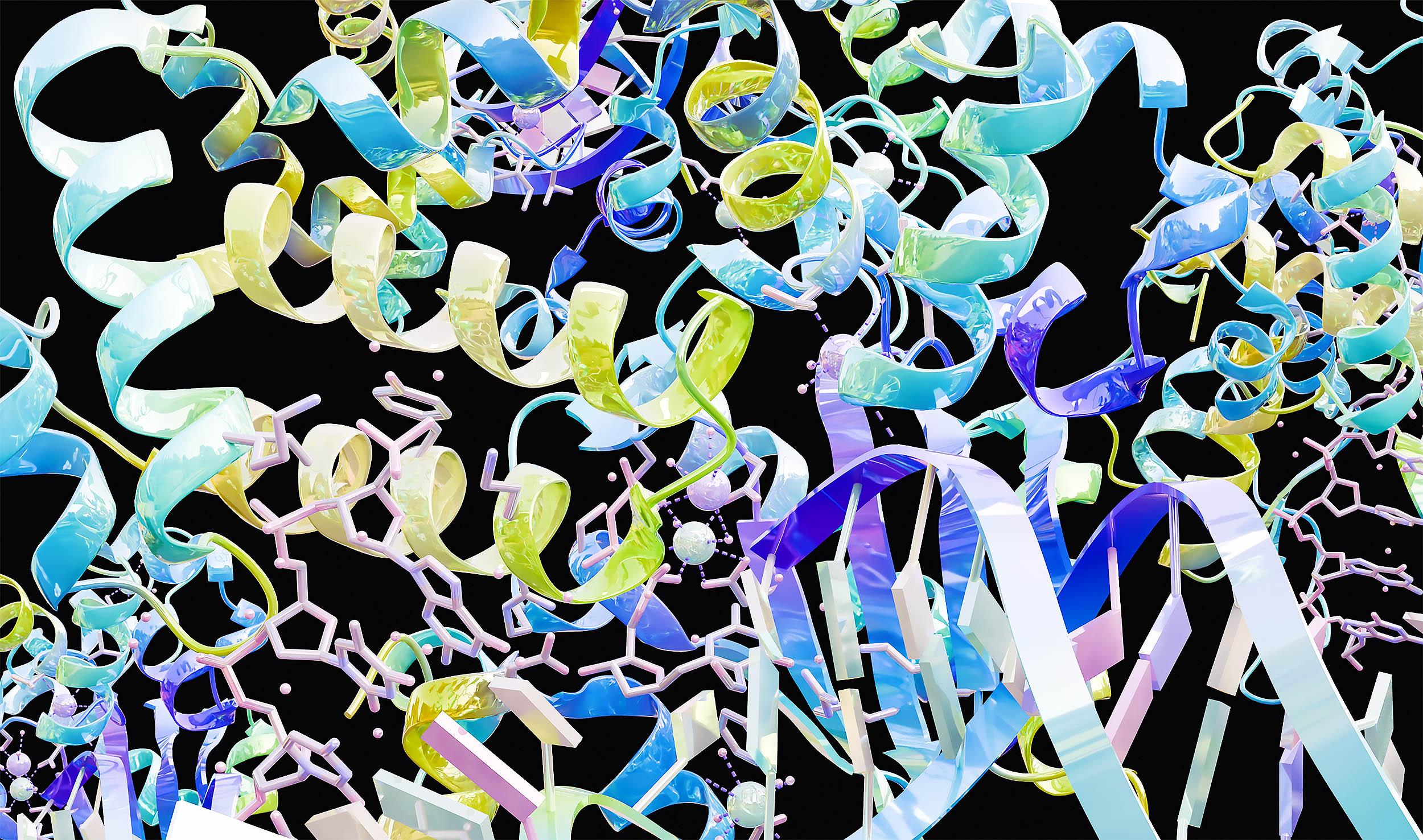

Scientists organize millions of proteins by conformation, as predicted by artificial intelligence, uncovering 700,000 new families and some forms unique to humans.

Using artificial intelligence and a new comparison method, scientists have just organized a huge collection of predicted protein forms.

Working with the alphabetic patterns scattered across the tree of life, they discovered approximately 700,000 previously undescribed groups of shapes and 13 that appear to be unique to humans.

Those structures are in the Alpha Fold Protein Structure Database, a public catalog of AI-predicted protein structures.

By sorting this vast structural library into related groups, researchers gain a clearer picture of how proteins function and evolve in the tree of life.

Seoul National University, led by Assistant Professor Martin Steineger of the School of Biological Sciences.

His research focuses on building ultrafast methods to compare large numbers of protein sequences and structures with creative computational shortcuts.

Before this work, most protein shape comparisons were done in small groups, where scientists studied one protein family or narrow group at a time.

Combining all the available models together creates a panoramic view of the protein space, revealing structural patterns that only emerge when the entire dataset is considered.

"We are entering a new era in structural biology where computational methods open unprecedented access to explore the protein universe," says Martin Steinegger, who leads the project.

He and his colleagues estimate that using previous methods to collect the same protein conformation data could take about a decade of continuous computing.

The AlphaFold artificial intelligence method uses a deep neural network to convert amino acid sequences into structures with accuracy up to several experimental measurements.

When combined with databases, this approach now provides structural models for more than 200 million proteins, including many cataloged sequences across biology.

In this study, the team used Foldseek Cluster, a structural alignment algorithm that encodes protein shapes into a compact alphabet, to efficiently organize the AlphaFold models.

These families capture the diversity of almost all protein structures in the database, dividing the vast sea of models into approximately 2.3 million representative groups.

Many of the smaller families lack functional labels for existing resources, making them potential homes for previously unknown activities and events.

Because the method runs in approximately linear time with respect to database size, it scales comfortably to hundreds of millions of entries rather than stalling.

Among the enormous number of protein shapesThe team concentrated on the dark clusters.This is a group of proteins that do not match any known folds.

From these, they selected tens of thousands of unique predictions with high confidence and looked for pockets that could bind small molecules or catalyze reactions.

A few small clusters appeared in only one species, consistent with the expectation of de novo gene birth, the development of new non-coding protein-coding genes.

Looking specifically at humans, the research team found very few clusters containing only human proteins, suggesting that truly valuable human folds are rare.

Instead, most human protein structures fall into clusters that stretch across the tree of life, showing how evolution uses old molecular components to synthesize new ones.

For testers, black clusters highlight areas where no structures have been measured in the lab, making them attractive targets for further work.

Some of the most striking clusters connect human immune proteins and bacterial proteins, suggesting shared structural solutions that predate complex animals.

Another interesting issue is related to gasdermins, a family of proteins that create holes in cell membranes during certain immune responses.That action is called pyroptosis, a process in which infected cells burst and produce stimulatory signals.

Structural comparisons in the new clusters place human gasdermins alongside their bacterial counterparts, showing that the central pore-forming domain is shared between many distant branches of life.

Another example involves human bactericidal permeability-increasing protein, an innate immune protein that binds bacterial endotoxin.

In structural clusters, BPI is located next to bacterial proteins that share the same overall architecture, suggesting that microbes can reprogram related designs for their own membrane biology.

This group binds human DNA proteins like AIM2 to proteins in gut bacteria, suggesting that parts of our immune system may come from ancient microbial detectors.

Because the sequence similarity between these distant relatives is often very low, their shared folds are almost impossible to detect by simply examining the sequences.

These long-range structural relationships are important because protein conformation changes more slowly than sequence, so protein structure often maintains evolutionary relationships long after sequence identity has been lost.

For researchers pursuing a specific role, the AlphaFold Clusters database now serves as an atlas, finding neighboring structures and generating new hypotheses about the proteins involved.

For drug discovery teams, dark clusters containing putative binding pockets appear particularly attractive because they may harbor enzymes or receptors untouched by any existing drugs.

The study was published in Nature.

What are you reading?Subscribe to our newsletter for interesting articles, exclusive content and the latest updates.

Check us out at EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.